- all persons of Indian blood, reputed to belong to the particular body or tribe of Indians interested in Lower Canada lands, and their descendants

- all persons married to such Indians and residing amongst them, and their descendants

- all persons residing among such Indians, whose parents on either side were or are Indians of such body or tribe or entitled to be considered as such

- all persons adopted in infancy by any such Indians and residing in the village or upon the lands of such body or tribe of Indians, and their descendants

1869: Legal modifications

- Indian women who married non-Indians are no longer considered Indians and children of the marriage are also not considered Indians under the act

- Indian women who marry an Indian man become a member of their husband's band

1876: Indian Act

- the first act to be clearly identified as an Indian Act in Upper and Lower Canada

- "Indian" was defined as:

- any male person of Indian blood reputed to belong to a particular band

- any child of such person

- any woman who is or was lawfully married to such person

- wives and children are automatically enfranchised along with their husband or father

1918: An Act to amend the Indian Act

- unmarried women and widows, along with their minor unmarried children could seek voluntary enfranchisement beginning in 1918

1919 to 1920: An Act to amend the Indian Act

- the provision to enfranchise Indians who acquired university education or religious orders was repealed in an amendment to the Indian Act in 1919-1920

1951: An Act respecting Indians

- the Indian Register was established to record all individuals entitled to registration

- the Indian Registrar can add or delete (if they are ineligible) names from the register

- individuals can protest additions or deletions from the register

- when a male is added or deleted from the register, his wife and children are also added or deleted

- women who marry a non-Indian man are not eligible for registration, and they were removed from band lists upon marriage

- individuals are eligible for voluntary enfranchisement if they meet specific requirements

- the wife and children of a man who is enfranchising must be clearly named on the order of enfranchisement to be removed from the register or they keep their status

- the double mother rule was introduced to remove status from grandchildren at age 21, whose mother and paternal grandmother both acquired status through marriage to an Indian

1985: Bill C-31, An Act to amend the Indian Act

- women do not automatically join their husband's band through marriage

- all enfranchisement provisions, both voluntary and involuntary, are removed and provisions are created to allow individuals, especially women who had lost status, to be reinstated as status Indians

- section 10 introduces the ability for Indian bands to determine their own membership codes and rules

- children are treated equally whether they are born in or out of wedlock, and whether they are biological or adopted

- the definition of "child" included in section 2 of the Indian Act was modified to recognize a legally adopted child (not only a legally adopted Indian child) and child adopted in accordance with Indian custom

2011: Bill C-3, Gender Equity in Indian Registration Act

- came into force in response to the McIvor v. Canada decision

- addressed inequities relating to the removal of the double mother rule under Bill C-31 in 1985 which created an added benefit for the male line of a family

- grandchildren of women who lost status due to marrying a non-Indian man prior to 1985 become entitled to registration for the first time

- introduced the "1951 Cut-Off" under section 6(1)(c.1)(iv)

2017: Bill S-3, Act to amend the Indian Act in response to the Superior Court of Quebec decision in Descheneaux c. Canada ( Procureur général )

- came into force in response to the Descheneaux c. Canada ( Procureur général ) decision

- provisions related to siblings, cousins, omitted or removed minors, and unknown or unstated parentage came into force on December 22, 2017

- provisions related to the removal of the 1951 cut-off will come into force at a later date after the consultation phase of the collaborative process

- First Nations, Indigenous groups and impacted individuals will be consulted on how to implement the removal of the 1951 cut-off

- see the Removal of the 1951 cut-off fact sheet

Section 6(1) and 6(2) registration

What is section 6?

Section 6 of the Indian Act defines how a person is entitled to be registered under the Indian Act. The federal government has the sole authority, through the Indian Registrar, to determine who is entitled to be registered. Persons registered with Indian status are eligible for services and benefits delivered through federal departments. Although registration is divided into two primary categories, which are commonly known as sections 6(1) and 6(2), individuals registered under sections 6(1) or 6(2) have the same access to services and benefits.

What is the difference between 6(1) and 6(2) status?

A person may be registered under section 6(1) if both of their parents are or were registered or entitled to be registered. There are 14 categories under section 6(1) which identify how someone is entitled for registration.

- the "double mother" provision

- the person was a woman who married a non-Indian

- the person is a child omitted or removed due to their mother marrying a non-Indian

- the person was removed by protest due to being the illegitimate child of a man who was not an Indian and a woman who was an Indian

There is no difference in access to services and benefits available to registered Indians whether an individual is registered under 6(1) or 6(2). However, the ability to pass Indian status differs depending on whether a parent is registered under 6(1) or 6(2).

How does entitlement to Indian registration work post-1985?

The following diagrams show different parenting scenarios and how those individuals would be registered:

Description of Figure 1a: Two parents registered under section 6(1)

Figure 1a presents two parents who are registered under section 6(1). The child of these parents is entitled to register under section 6(1).

Description of Figure 1b: Two parents registered under section 6(2)

Figure 1b presents two parents who are registered under section 6(2). The child of these parents is entitled to register under section 6(1).

Description of Figure 1c: One parent registered under section 6(1) and one parent registered under section 6(2)

Figure 1c presents one parent who is registered under section 6(1) and one parent who is registered under section 6(2). The child of these parents is entitled to register under section 6(1).

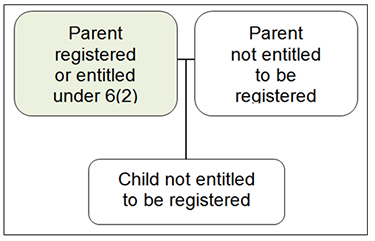

Description of Figure 1d: One parent registered under section 6(1) and one parent not entitled to be registered

Figure 1d presents one parent who is registered under section 6(1) and one parent who is not entitled to be registered. The child of these parents is entitled to register under section 6(2).

Description of Figure 1e: One parent registered under section 6(2) and one parent not entitled to be registered

Figure 1e presents one parent who is registered under section 6(2) and one parent who is not entitled to be registered. The child of these parents is not entitled to register. This is known as the second-generation cut-off.

If a person registered under section 6(1) has a child with a person not entitled to registration (non-Indian), their child is entitled to registration under 6(2): Figure 1d. If a person registered under section 6(2) has a child with a person not entitled to registration (non-Indian), their child will not be entitled to registration: Figure 1e. Entitlement to registration under the Indian Act is lost after two successive generations of parenting with a person not entitled to registration (non-Indian). This is commonly known as the second-generation cut-off and was introduced in the 1985 Bill C-31 amendments. For more on the second-generation cut-off please see:

What makes section 6 an important issue?

The creation of a division of entitlement to registration under sections 6(1) and 6(2), as well as the further breakdown of section 6(1) into various sub-categories has resulted in the perception of one category of registration being better than others. For example, many women who were re-instated under section 6(1)(c) following the 1985 amendments were labeled and treated differently (often negatively) than individuals who were entitled under section 6(1)(a). Although there is no difference in access to government services and benefits available to registered Indians whether an individual is registered under 6(1)(a) or 6(1)(c) or section 6(2), there exists a perception that being registered under 6(1)(a) is better or the most desired category. The only legal difference, as defined by the Indian Act , based on the category an individual is registered under is in their ability to pass on entitlement to registration to their children depending on who they parent with. If an individual registered under section 6(1) parents with a non-Indian, their children will be entitled under section 6(2). If an individual registered under section 6(2) parents with a non-Indian, their children will not be entitled to registration.

For First Nations that control their own membership under section 10, their membership code defines who is entitled to membership. Some membership codes differentiate eligibility for membership by the category an individual is registered under. This subsequently results in registered individuals being treated differently by First Nations in determining who can be band members depending on the category they are registered under.

This perceived hierarchy or viewpoints that there are "better" categories of registration is often described by some as being discriminatory. This can create lines drawn within families and disconnection of community and family ties if individuals are not registered under the "right" category.

Bill C-31 and Bill C-3 amendments

What is Bill C-31?

In 1985, the Indian Act was amended through Bill C-31 to eliminate discriminatory provisions and ensure compliance with the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (the charter). As part of these changes:

- Indian women who married a non-Indian man no longer lost their Indian status

- Indian women who had previously lost their status through marriage to a non-Indian man became eligible to apply for reinstatement, as did their children

- non-Indian women could no longer acquire status through marriage to an Indian man

- non-Indian women who had acquired status through marriage prior to 1985 did not lose their status

- the process of enfranchisement was eliminated altogether as was the authority of the Indian Registrar to remove individuals from the Indian Register who were entitled to registration

- individuals who had been previously voluntarily or involuntarily enfranchised under the Indian Act could apply for reinstatement

Involuntary enfranchisement:

Enfranchisement occurred without the consent of the individual(s) concerned.Voluntary enfranchisement:

An individual made an application to prove they were "civilized" and able to take care of themselves without being dependent upon the government.The federal government retained control over Indian registration and new categories of registered Indians were established within the Indian Act through sections 6(1) and 6(2). The second-generation cut-off was introduced where after two consecutive generations of parenting with a person who is entitled to registration and a person who is not entitled to registration (non-Indian), the third generation is no longer entitled to registration.

The Bill C-31 amendments were an attempt to establish equality between men and women by creating a standard free of sex-based distinctions in the transmission of Indian status, taking into account First Nations concerns around financial considerations and the protection of the ethno-cultural integrity of First Nations. The principles and rationale for the inclusion of the second-generation cut-off was an attempt to balance individual and collective rights.

New authorities to determine band membership were also introduced with Bill C-31 under sections 10 and 11 of the Indian Act : section 10 allowed bands to determine and control their membership if they meet certain conditions. Under section 11, the Indian Registrar administers the band lists for bands that do not seek control of their membership under section 10.

What were the impacts of Bill C-31?

Registration

The 1985 Bill C-31 amendments did address some sex-based discrimination. However, because an individual's entitlement to registration is based on the entitlement of their parents and previous ancestors, residual sex-based discrimination stemming from past Indian acts were carried forward.

New issues arose as a direct result of the introduction of the categories under sections 6(1) and 6(2), and the creation of the "second-generation cut-off". Inadvertently, the creation of the different categories of registration resulted in the perception among many First Nations that some categories were "better" or "worse" than others.

Membership

With the introduction of two systems for membership under sections 10 and 11, the relationship between Indian registration and band membership began to diverge. For section 10 bands, registration and membership were no longer synonymous, whereas for bands under section 11, they remain connected. As a result, there are situations where an individual is not entitled to registration pursuant to the Indian Act but, because they originate from a section 10 band whose membership rules are more expansive, non-registered individuals can be a band member, and vice-versa.

Funding

Over 174,500 individuals became newly registered to registration under Bill C-31. Federal funding did not keep up with the influx in membership and as a result, funding pressures increased for band councils to provide programs and services to an increasing number of individuals newly entitled to registration and membership.

What is Bill C-3?

Challenges under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms alleging continued residual sex-based and other inequities in the Indian Act registration provisions were launched relatively soon after the passage of Bill C-31. The first of these challenges, launched in 1987, was the McIvor case. The plaintiff, Sharon McIvor, had lost entitlement to registration when she married a non-Indian man and was reinstated under section 6(1)(c) following the 1985 amendments to the Indian Act. Her son, Jacob Grismer, having only one Indian parent, was entitled to registration under section 6(2) but was unable to transmit that entitlement to his children due to parenting with a non-Indian woman. In contrast, Jacob's cousins in the male line born to a man who married a non-Indian woman before 1985 could pass on their status irrespective of the status of the other parent.

The McIvor case was decided by the British Columbia Court of Appeal (BCCA) in 2009. In its decision, the BCCA expanded the definition of Indian and eligibility for Indian registration under the Indian Act . The McIvor decision prompted further legislative amendments to the Indian registration provisions of the Indian Act through the Gender Equity in Indian Registration Act (Bill C-3). Bill C-3 amendments resulted in certain individuals previously entitled to registration under section 6(2) such as Mr. Jacob Grismer, becoming entitled for registration under section 6(1)(c.1) of the Indian Act as long as they met all the following criteria:

- have a mother who had lost her entitlement to registration as a result of marrying a non-Indian prior to April 17, 1985

- have a father who is not entitled to be registered, or if no longer living, was not at the time of death entitled to be to be registered

- was born after the date of their mother's marriage resulting in loss of entitlement for their mother and prior to April 17, 1985 (unless their parents were married prior to that date)

- have had or adopted a child on or after September 4, 1951 with a person who was not entitled to be registered on the day on which the child was born or adopted

By amending registration under section 6 (1)(c.1) for these individuals, their children subsequently become entitled to registration under section 6(2) of the Indian Act if they have:

- a grandmother who lost her entitlement as a result of marrying a non-Indian

- a parent entitled to be registered under section 6(2)

- a birth date or had a sibling born on or after September 4, 1951

As a result, more than 37,000 newly entitled individuals were registered from 2011 to 2017 through the implementation of Bill C-3.

The charts below demonstrate the differences in the entitlement of siblings (brother and sister) when the sister regained entitlement to registration following a marriage to a non-Indian man before April 17, 1985 under Bill C-31 and then the same situation following the changes to under the Gender Equity in Indian Registration Act (Bill C-3). Both the brother's and sister's children are now entitled under section 6(1) and the grandchildren are entitled under section 6(2).

Description of Figure 1a: Bill C-31 amendments (1985)

Figure 1a describes the situation of a brother and sister registered under section 6(1) where both siblings married non-Indians. Prior to 1985, the sister lost entitlement to status following marriage to a non-Indian. The brother retained his status under section 6(1). The child of the brother and the child of the sister both married non-Indians. The brother's child retains status under section 6(1) and the brother's grandchild retains status under 6(2). After the sister regains her status under the amendments of Bill C-31, her child gains status under section 6(2) but the sister's grandchild is not entitled to status. The family lines are unequal.

Description of Figure 1b: Bill C-3 amendments (2011)

Figure 1b describes the situation of a brother and sister registered under section 6(1) where both siblings married non-Indians. The sister lost her entitlement to status under previous versions of the Indian Act but regained status under section 6(1) through the amendments in Bill C-31. The child of the brother and the child of the sister both married non-Indians. The brother's child retains status under section 6(1) and the brother's grandchild retains status under 6(2). After the amendments of Bill C-3, the sister's child gains status under section 6(1) and the sister's grandchild gains status under 6(2). The family lines are equal.

Bill S-3 amendments

What is Bill S-3?

In response to the Superior Court of Quebec decision in the Descheneaux case, the Government of Canada introduced Bill S-3 to correct sex-based inequities in the registration provisions of the Indian Act . The Superior Court of Quebec ruled that provisions relating to Indian registration under the Indian Act unjustifiably violated equality provisions under section 15 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms because they perpetuated a difference in treatment between Indian women as compared to Indian men and their respective descendants.

Canada accepted the decision and launched a two-part response, including:

- legislative reform with Bill S-3 to eliminate known sex-based inequities in Indian registration

- a collaborative process on Indian registration, band membership and First Nations citizenship

Changes from An Act to amend the Indian Act in response to the Superior Court of Quebec decision in Descheneaux c. Canada ( Procureur général ) (Bill S-3) come into force at two different times:

- those in direct response to the situations identified by the Superior Court of Quebec in the Descheneaux case that took effect on December 22, 2017

- those that will come into force at a later date after consultation

What are the major changes that came into effect in December 2017?

The changes that came into force in December 2017 ensure that eligible grandchildren and great-grandchildren of women who lost status as a result of marrying a non-Indian man become entitled to registration in accordance with the Indian Act . It also ensures children born female and out of wedlock would be entitled to registration as well as their descendants going back to 1951. See a breakdown of the specific changes in the chart below.

- both the male and female children who were born out of wedlock of Indian men will now be entitled to be registered under section 6(1)

- the descendants of men and women are now treated the same

- consultation must begin by June 12, 2018

What are the amendments that will take effect after consultation?

The amendments that will come into force at a later date, following consultation, relate to the removal the 1951 cut-off from the registration provisions in the Indian Act . Once these delayed provisions are in force, all descendants born prior to April 17, 1985 (or of marriage that occurred prior to that date) of women who were removed from band lists or not considered Indians because of their marriage to a non-Indian man prior to 1951 will be entitled to status, allowing the ability to further transmit entitlement to their children. This will remedy inequities back to the 1869 Gradual Enfranchisement Act.

The consultation process will address the implementation of removing the 1951 cut-off and the broader issues of Indian registration, band membership and First Nations citizenship. The consultation process was co-designed with First Nations and Indigenous organizations.

What is the plan for the collaborative process?

Consultations under the collaborative process will address three streams:

- the removal of the 1951 cut-off from the Indian Act

- remaining registration and membership inequities under the Indian Act

- discussions around how First Nations will exercise their responsibility for the determination of the identity of their members or citizens, and Canada getting out of the "business" of determining status under the Indian Act

Comprehensive consultations were launched on June 12, 2018 and will complete with a report to parliament due by June 12, 2019.

Demographic impacts of past Indian Act amendments

Demographic overview

As of March 2018, the total registered Indian population was 990,435 (502,953 women and 487,482 men). Of that population, it is estimated that 510,430 reside on reserve and 480,005 live off reserve.

Description of Figure 1: 2018 registered Indian population by province

Figure 1 presents a map of Canada. The map is based on an analysis of data from the March 2018 Indian Register. The map is colour coded according to the population of the province or territory. The population totals are as follows:

- Alberta: 128,814

- British Columbia: 147,124

- Manitoba: 159,452

- New Brunswick: 16,161

- Newfoundland and Labrador: 30,637

- Northwest Territories: 19,444

- Nova Scotia: 17,397

- Ontario: 213,717

- Prince Edward Island:1,348

- Quebec: 89,196

- Saskatchewan: 157,670

- Yukon: 9,475

Previous demographic impacts from legislative amendments to the Indian Act

The 1985 Bill C-31 amendments to the Indian Act resulted in an increase of the population entitled to Indian registration of 174,500 from 1985 to 1999. Most of this growth occurred through reinstatements and new registrations (106,781) as well as children born since Bill C-31 who would have not qualified under previous acts (59,798). The 2011 Bill C-3 amendments to the Indian Act resulted in more than 37,000 newly entitled individuals registered from 2011 to 2017 who would have not qualified under previous acts.

Immediate impacts of Bill S-3: cousins, siblings, and omitted minors remedies

Based on an analysis using information from the Indian Register on July 2016, Bill S-3 amendments to the Indian Act are expected to increase entitlement to Indian registration by 28,970. The majority of this increase comes from the cousins remedy (25,588), followed by the siblings remedy (2,905) and omitted minors (477). It is expected that 4,557 individuals entitled to registration under section 6(2) will become entitled under section 6(1).

Immediate impacts of Bill S-3 excluding unstated paternity

On reserve Off reserve Total entitled 689 28,282 28,961 Source: Based on analysis of data from the July 2016 Indian Register This increase in entitlement to Indian registration will also apply to band membership. Of the estimated 28,961 newly entitled, 17,260 would be entitled to membership under section 11 bands and will automatically become a member when registered under the Indian Act . The remaining 10,533 would be affiliated with section 10 bands and could attain membership by application, if they qualify under the individual band membership codes. The remaining 1,168 would be connected to bands under self-government legislation or appear on the general lists (not affiliated with a band).

Delayed impacts of Bill S-3: removing the 1951 cut-off

The amendments that come into force at a later date will remove the 1951 cut-off from the Indian Act . During the collaborative process, Canada will be consulting on the implementation of the removal of the 1951 cut-off. Upon completion of this process, an implementation plan will be prepared, and the process will begin to bring this amendment into force.

There is significant uncertainty around determining the population impacts for the removal of the 1951 cut-off as there is no data set that can directly identify the number of individuals that could be impacted. Since the Indian Register only came into existence in 1951, crude estimates of the impact of this amendment can only be obtained using the number of individuals who self-reported Indigenous ancestry from the 2016 Census of Canada.

It is estimated that between 750,000 and 1.3 million individuals in Canada could be entitled to registration under Bill S-3 based on the number of individuals who self-reported as having North American Indian ancestry or identity on the 2016 Census. These numbers are not reflective of how many individuals would eventually apply for Indian registration and likely overestimates the number of individuals who would become registered. The Parliamentary Budget Officer's report PDF format (369 Kb , 25 pages) on the demographic impacts of delayed amendments to the Indian Act estimated that 270,000 individuals could become registered.

Related links

Footnotes

Footnote 1The term "Indian" is used to reflect the language used in legislation, such as the Indian Act , both historically and today.

The double-mother rule was introduced in the 1951 Indian Act and removed status from grandchildren at age 21, whose mother and paternal grandmother both acquired status through marriage to an Indian. The rule was repealed in 1985 under Bill C-31.

Applies also when an individual was born after April 16, 1985 of parents married before April 17, 1985.

The double-mother rule was introduced in the 1951 Indian Act and de-registered grandchildren at age 21, whose mother and paternal grandmother both acquired status through marriage to an Indian. The rule was repealed in 1985 under Bill C-31.

Thank you for your feedback