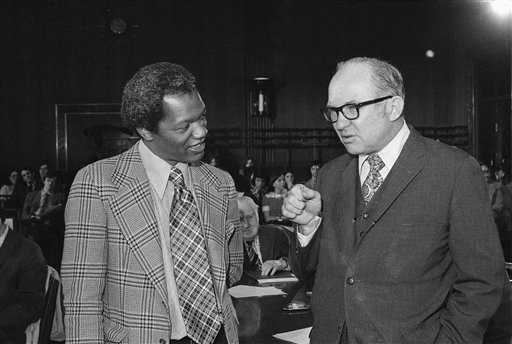

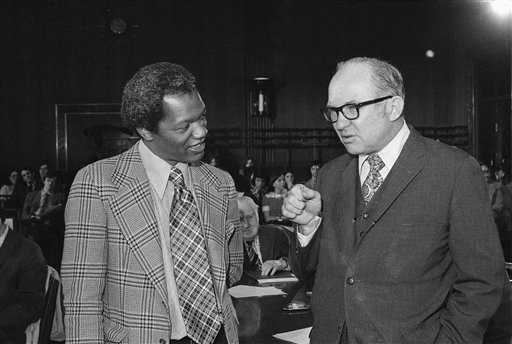

Reporter Earl Caldwell of the New York Times, left, was involved in a case that went to the Supreme Court concerning whether a reporter's privilege existed to protect journalists from being forced by the government to reveal information that they learned in reporting. The FBI tried to get him to reveal information he learned through his reporting on the Black Panthers. The Supreme Court in a narrow decision in Branzburg v. Hayes refused to recognize such a reporter's privilege based on the First Amendment. This photo of Caldwell, talking with syndicated columnist James Kilpatrick was taken in 1973 prior to Caldwell delivering testimony before a U.S. Senate subcommittee that was investigating freedom of the press. (AP Photo/Henry Griffin, used with permission from the Associated Press.)

The idea behind reporter’s privilege is that journalists have a limited First Amendment right not to be forced to reveal information or confidential news sources in court.

Journalists rely on confidential sources to write stories that deal with matters of legitimate public importance. Many reporters believe that the First Amendment provides them protection from testifying before a grand jury regarding their sources and prize their role as “neutral watchdogs and objective observers.” According to the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, courts traditionally have supported the idea that individuals may refuse to testify when there is a determination that the interests of society outweigh the need for full disclosure of evidence.

In Branzburg v. Hayes (1972), the Supreme Court considered three consolidated cases determining whether there is a constitutionally based privilege in the First Amendment that permits reporters to refuse to testify before a grand jury.

In 1971 Paul Branzburg, a reporter for the Louisville Courier Journal, was called before a grand jury to testify about drug use in Kentucky after he had written two articles on the subject. In a second case, Paul Pappas, a reporter for a Massachusetts television station, was asked to tell a grand jury what he had seen and heard at a Black Panther office in 1970. In the third case, Earl Caldwell, a New York Times reporter who was African American and had gained the confidence of the Black Panthers in Oakland, California, was subpoenaed to appear before a grand jury investigating the activities of the group.

In its ruling, the Court split three ways.

Justice Byron R. White, in writing the Court’s opinion, was joined by three other justices who saw no First Amendment privilege for reporters called to testify before a grand jury. White, although acknowledging the protections of the First Amendment, did not find that Branzburg had been denied any of them.

According to White, “The use of confidential sources by the press is not forbidden or restricted… The sole issue before us is the obligation of reporters to respond to grand jury subpoenas as other citizens do and answer questions relevant to an investigation into the commission of a crime.”

The four dissenters in the case were William O. Douglas, Potter Stewart, William J. Brennan Jr., and Thurgood Marshall. Douglas saw the First Amendment as giving the press an “absolute and unqualified” First Amendment protection; the other three dissenters saw only a protection that is qualified, not absolute.

The dissenters proposed a three-pronged guideline to protect the identity of a confidential source.

Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr. rendered the fifth vote necessary for the high court to reject the notion of a constitutional privilege for reporters.

State shield laws are a statutory protection that gives journalists privilege against forced production of confidential or unpublished information. There is no federal shield law. In this photo, New York Times reporter Judith Miller, center, speaks at a panel discussion during a journalism conference in Las Vegas in 2005. Miller, who was jailed 85 days for refusing to reveal a source, defended her decision to go to jail to protect a source. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong, used with permission from the Associated Press)

According to the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, state courts, state constitutions, and common law have generally exercised three options in this area.

First, many states have recognized a reporter’s privilege under state law. New York’s highest court, for example, has recognized a qualified privilege based on its state constitution — protecting both confidential and nonconfidential materials.

Second, in other states, a reporter’s privilege is based on common law. For example, the Supreme Court of Washington state recognized a qualified privilege in civil cases initially and later in criminal cases.

In a third option, courts in some states, among them New Mexico, can create their own rules of procedure.

Furthermore, in the absence of a court-recognized privilege, or applicable shield law, journalists have successfully persuaded courts to quash subpoenas on the basis of generally applicable laws, including state rules of evidence.

Yet another option is a statutory protection that gives journalists privilege against forced production of confidential or unpublished information. Forty-nine states and the District of Columbia have enacted such statutes, called shield laws. These statutes tend to give more protection to reporters than does the federal Constitution or state constitutions. Shield laws have limitations, however. For example, in some states a reporter forfeits the privilege if he or she discloses a portion of the confidential matter in question. In a few states, shield laws are not applicable unless confidentiality is understood between a reporter and the source.

In 2005, then- U.S. Rep. Mike Pence, R-Indiana, introduced the Free Flow of Information Act. (Pence became vice president of the United States in 2017.) The goal of the bill is “to maintain the free flow of information to the public by providing conditions for the federally compelled disclosure of information by certain persons connected with the news media.” The House Judiciary Committee passed a later version of the bill in 2007. However, the measure did not pass.

Pence and others introduced similar measures in 2009, 2011, and 2013. In 2013, the measure passed the House, but the bill never made it to the Senate floor for a vote.

In 2017, U.S. Rep. Jim Jordan, R-Ohio, and U.S. Rep. Jamie Raskin, D-Maryland, renewed the effort for a federal shield law with a new bill with similar elements.

After criticism over the U.S. Justice Department’s use of subpoenas and other investigative tools to gather information from or about journalists during leak investigations, the Justice Department in 2022 updated its guidelines on obtaining journalists’ records to prohibit the use of such tools, with narrow exceptions. The policy prohibits the use of a compulsory legal process to gather information from or about a member of the news media who has “in the course of newsgathering, only received, possessed, or published government information, including classified information, or has established a means of receiving such information, including from an anonymous or confidential source.”

The policy shift came after it had come to light in 2021 that the Trump Justice Department had secretly seized the phone records of journalists with the Washington Post, The New York Times and CNN who had reported on federal investigations related to the 2016 presidential campaign.

In 2023, a federal judge in Washington, D.C., weighed whether to hold in contempt a veteran journalist who has refused to identify her sources for stories about a Chinese-American scientist who was investigated by the FBI but never charged.

In that case, Yanping Chen v. Federal Bureau of Investigation, Chen, the scientist, alleges the government violated the Privacy Act is releasing documents about her. After not being successful through discovery with the government to determine who leaked the documents, she subpoenaed the journalist, Catherine Herridge, and Fox News, Herridge's employer at the time.

In a ruling on Aug. 1, 2023, the federal judge allowed Chen to depose Herridge as to the identity of her sources. Herridge refused to reveal her source or sources. As of Nov. 14, 2023, the judge had not ruled on whether to hold Herridge in contempt of court for not revealing her source.

This article first was published in 2009 and last updated in November 2023. The primary contributor was John Omachonu. It has been updated by other First Amendment Encyclopedia contributors.